It is natural to look at brilliant designs by Paul Rand, Saul Bass or David Carson and to want to create designs like that – or even to want to be as great as them. This inspiration is what has reeled many of us into the field of graphic design. For some, it leads nowhere. For others, it unearths a true passion for design and occasionally it brings a brilliant designer into the limelight.

Inevitably, greatness is a status that occasionally churns in the back of a graphic designer’s subconscious. This article brings the concept of greatness to the forefront and breaks it down by looking at commonalities between the all time great graphic designers; both in talent and fame. This list is a good starting point for anyone questioning their status in graphic design.

Theory

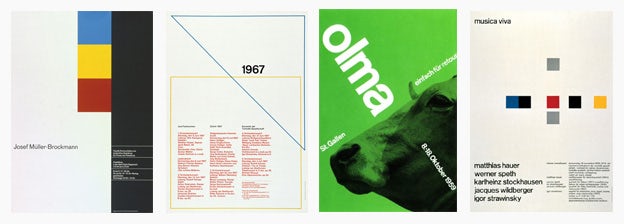

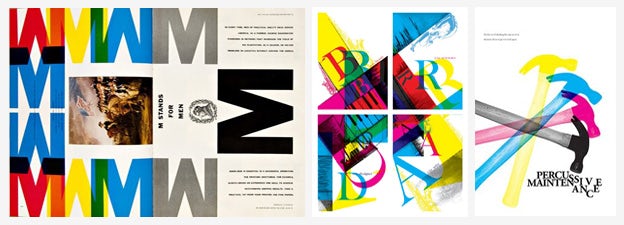

Design Works: Josef Müller-Brockmann

Graphic design is largely subjective. There is no single design work that every observer has enjoyed. People enjoy different things, naturally. There are however commonly accepted theories about graphic design; ideas that formulate the essence of strong design work. They assist in the articulation of what makes great graphic design, and they serve as an extension of reach in design ability.

A common thread between all great graphic designers is that they either had a heavy hand in the formation of graphic design theory, or it is easily identified in their work. Josef Müller-Brockmann is a perfect example of this component. His 1981 publication Grid Systems in Graphic Design laid down the fundamentals of grid use and would be referenced by many for years to come.

The Brockmann examples above depict his mastery of grid use, notably in the second example from the left where he intentionally breaks the grid along the bottom right edge with a vertical dissonance to strike a wonderful visual intrigue.

Technical skill

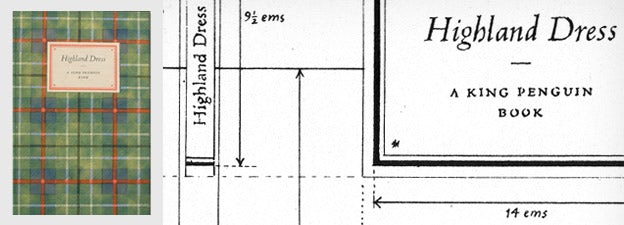

Penguin Branding Handbook & Example Cover: Jan Tschichold

Technical skill is what allows a graphic designer to materialize their ideas into reality. It is a skill of both the hand and of the mind. In hand, it includes using tools such as a pencil, an ellipse guide or a computer trackpad (to name a few). In the mind, it includes operations such as math, measurement or color adjustment.

All great designers possess a high degree of technical skill in at least one realm of graphic design. There is perhaps none better to exemplify this than Jan Tschichold. His obsession with typography and book layout was fueled by unparalleled technical skill.

Pictured above is an example from Tschichold’s Penguin branding guide, where the exacting proportions he demanded of the Penguin layout staff can begin to be seen.

Intuition

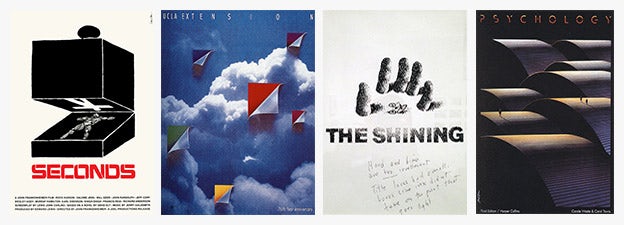

Design works: Saul Bass

This component could also be called the “it” factor. Some people have it and some don’t. It is a trait that stems from a passionate curiosity in design that goes beyond earning money or holding a career. It is where the perception of design truths are, in part, independent of a reasoning process. Decisions are made not only in theory or technicality, but in artistic inspiration and expression.

Intuition is a quality shared by all great designers and is ever-present in the work of Saul Bass. In the examples featured above, note how the strength in design is felt more viscerally and emotionally than intellectually. Theory and technical skill alone cannot bring one to the places which Bass has arrived. These destinations require a willingness to become artistically unconscious; a willingness to trust one’s intuition.

Resources

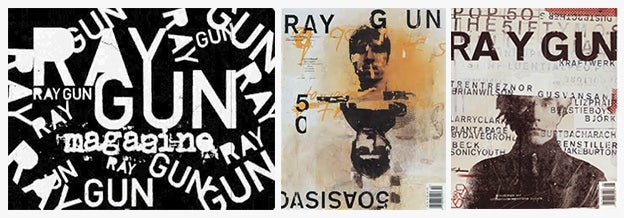

Design Works: David Carson

Graphic design is a resource heavy field. In the analog domain resources partially include print making tools, assorted paper, scissors, matt knives, rulers, ellipse guides and found materials. In the digital domain recourses partially include computers, design programs, font files, internet connection, mock up templates and texture libraries. Without resources, designers are simply containers for their thoughts and feelings.

Every great designer has, or had, a plentiful supply of resources. Take for example David Carson and his work for Ray Gun magazine. His approach to this work was clearly very hands on. He was likely cutting, painting, layering and print-making. Imagine what his workspace looked like for these projects. Access to resources was a big part of what enabled him to break new design ground and change the landscape of design, typography especially.

Personality

Design Works: Paul Rand

In the history of graphic design there are few designers who’s work is so individualistic that it can be effortlessly identified in a crowd. Because humans seek personality, character and life force, that recognition is largely triggered when the personality of the designer shows through in their design work.

Paul Rand’s personality and his design work were one in the same. His signature color palettes, playful-yet-serious sensibility and imperfect shapes all spoke to who he was as a person. This may play a large part in why he is loved both in and out of design circles.

Revolutionary

Design Works: Bradbury Thompson

When a person questions what is considered normal, alters what society is familiar with and forges new ideas from leaps of faith, they have in their grasp the attention of the masses. Witnessing a person disrupting and constructing simultaneously is both beautiful and unforgettable.

All great designers were revolutionary in some way. They all changed the game. One notable designer in this regard is Bradbury Thompson. During a time when CMYK was strictly part of print production, he embraced it as part of the creative process; an undiscovered artistic medium. Rather than using these colors to accurately reproduce photographs or shades of a certain color, he saw them as four colors on a palette. This epiphany was followed by an unforgettable body of work that is enjoyed by many to this day.

Publicity

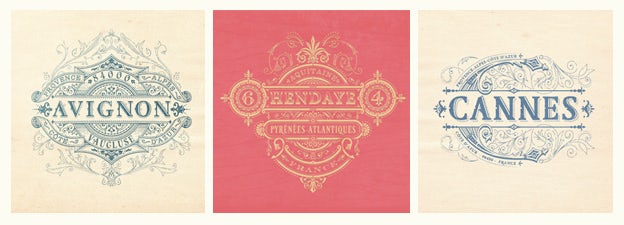

Design Works: Jean-Charles Desevre

In the 70s, fame was a byproduct of the qualities outlined above. This was likely due to the demand for graphic designers and the fact that, quite simply, there weren’t as many as there are today. Now, however, talent and fame do not come in a package deal. In 2012 there were roughly 259,500 graphic designers in the United States alone. The amount of design work being done around the world at this very moment is astronomical.

It takes more than incredible design work to stand out amongst millions. It takes a will power to climb to the top, self promote and land a job for a famous studio such as Pentagram. Being an incredible revolutionary designer is now only half the battle.

Take, for example, French designer Jean-Charles Desevre (work featured above). In the field of ornate logo design he is unrivaled and in a world of his own. It could be argued that he possesses all of the qualities outlined above, yet he seemingly remains a humble freelancer in France. But perhaps this is alright…

Final thoughts

Talent is an objectively necessary trait for any great graphic designer. But is fame still a relevant component of greatness today? Perhaps all along it was simply an ego feeder that existed independently from the essence of graphic design. Maybe now, it’s enough to simply be a talented graphic designer.

Possibly, if born into the modern era, Josef Müller-Brockmann, Jan Tschichold, Saul Bass and the others would have been perfectly happy being brilliant and modest freelancers similar to Jean-Charles Desevre. After all, it’s not the joy or even the pay that has nearly vacated graphic design today – only the fame and popularity.

Cover: IBM by Paul Rand